What do we mean by ‘response to treatment’ in rheumatoid arthritis? – Dr Seema Sharma speaks to Arthritis Digest

Arthritis Digest is a magazine for people with arthritis that highlights the latest relevant research and reviews topical issues.

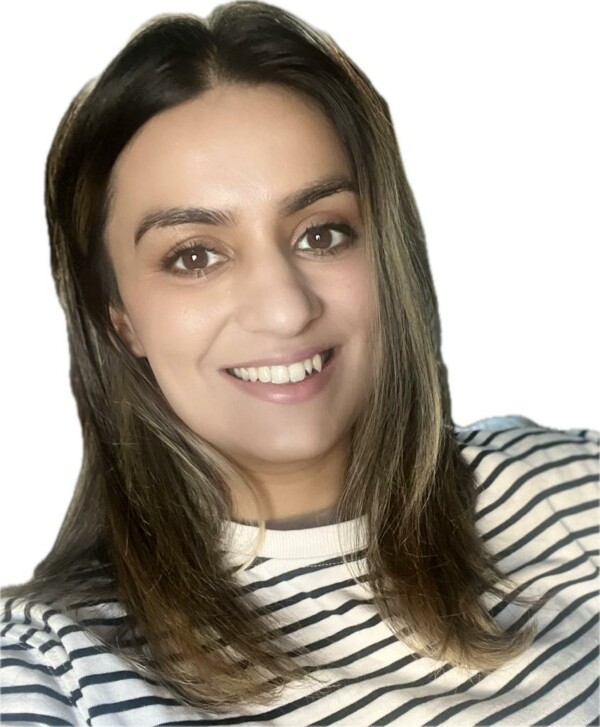

Continuing regular contributions from our Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases theme researchers, Dr Seema Sharma explains what ‘response to treatment’ means and how using it in research can lead to more positive outcomes for people with rheumatoid arthritis. Dr Sharma is a Clinical Research Fellow in the Centre for Musculoskeletal Research at The University of Manchester and an Honorary Clinical Fellow at North Manchester General Hospital, part of Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust.

Quality of life for people with rheumatoid arthritis is better than it has ever been. Even more effective treatments are tantalisingly close due to exciting new research. Personalised medicine is finally within reach, and could be set to transform the lives of people with rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune conditions.

What is rheumatoid arthritis?

Rheumatoid arthritis is a type of autoimmune disease, which means the immune system mistakenly damages healthy cells in the body.

Its most common symptom is usually painful swelling of the joints. Most often the hands and wrists are affected, but various joints can be impacted. Many people with this condition experience morning stiffness, which can make it diffcult to start the day.

Rheumatoid arthritis affects around 400,000 adults in the UK and is a long-term condition. There is currently no cure and treatments aim to control the inflammation responsible for symptoms. These are referred to as DMARDs which stands for disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. As well as providing relief from symptoms, the goal of these medications is to prevent long-term damage to the joints.

What does response to treatment mean?

It is an exciting time for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Through research, we know more about the underlying mechanisms of the disease than ever before. There has been significant advancement in in treatment options. However, it is not always clear which of these medications is most likely to work for each patient’s disease.

One of the most commonly used first choice treatments is methotrexate. Methotrexate is a traditional DMARD and has been used to treat rheumatoid arthritis for many years. For about half of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis, methotrexate controls the disease.

So for at least half of people, methotrexate does not adequately control the disease. Some patients are then treated with other medications known as biologic medications, which work on different pathways in the immune system.

One size does not fit all

Everyone’s disease is unique, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution; what works well for one patient may not work well for another.

In current clinical practice, we try different medications using a trial-and-error approach and consider switching treatments when one does not work. Approaches to understand and predict how suited a treatment is for an individual is referred to as personalised medicine.

To get the best outcome, we need to find the right treatment through regular check-ups and adjustments, whether it is a single medication or combination of treatments for each person. We also need to consider factors important to the patient. These include how often a medication is given and how it is administered. Some treatments are given in tablet form, others via a self-injection at home and some require administration in the hospital. Many individuals with rheumatoid arthritis may have additional medical conditions which must be factored into the decision-making process.

Making a call

Considering all of these important points, how do we decide when a treatment is working? Or perhaps more pressingly, how do we decide that a treatment is not working and we should consider making a change?

When we discuss assessing response to treatment, we are referring to the process of checking how well a chosen medical approach is working. Having ways to assess response to treatment is also important for research to determine the effectiveness of new medications. A reliable way to assess response to treatment ensures that we can tailor treatment for each patient and helps maximise the chance of symptom control, as well as preventing unnecessary changes in therapy.

How do we assess if a medication is working?

One of the most commonly used tools is the 28 joint disease activity score (DAS-28). This is used by healthcare professionals to assess how active the disease is. In other words, it is a way of evaluating the intensity of the symptoms and inflammation in the body caused by rheumatoid arthritis at a given moment in time. It is made up of four components:

- Tender joint count. By pressing and moving specific joints, we count how many joints are painful.

- Swollen joint count. By observing and examining specific joints, we count how many joints are swollen.

- Acute phase reactants. Blood tests measure specific markers of inflammation. C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) can be used.

- Patient global assessment. A score given by the patient, normally out of 10 or 100, assesses their overall wellbeing and the impact they feel rheumatoid arthritis is having on their life.

Each of these components are put into an online calculator which gives an overall score. The higher each of the components are, the higher the overall score. This provides us with a numerical way to compare between visits how a patient is doing and we can evaluate whether disease activity is high, medium, low or in remission. By looking at how the scores change over time, it helps us to see how well a treatment is working for a patient.

Missing information

While DAS-28 is helpful, it does not always tell the full story. It may overlook important factors of a person’s disease, such as levels of fatigue and extent of morning stiffness. In some cases, rheumatoid arthritis affects areas of the body beyond the joints, which is not captured in this score.

The DAS-28 Score can also be impacted by other factors. For example, joint tenderness may be influenced by other causes of joint pain including fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis and psychological factors.

Markers of inflammation measured by blood tests (CRP and ESR) can go up for reasons other than rheumatoid arthritis; for example, infections and other autoimmune diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease may cause the blood tests to be high.

Where DAS-28 is high, it is important to consider whether this is due to a flare up of rheumatoid arthritis, or if other factors may be driving it. This is especially important when we are making decisions about adjustment of treatments. Making a change in treatment based only on a high DAS-28 without considering a patient’s individual context could lead to unnecessary changes in treatment which may not be best way forward.

How does this affect research?

One of the research areas I am interested in is whether we can predict if a person may respond to treatment by studying their genetics. Genes are small sections of our DNA, which can be thought of as a biological blueprint. Our genetic code provides instructions for what makes a person. Researchers have found that certain differences in genes can contribute to how likely one is to develop diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, as well as influencing the severity of disease and response to treatment.

The nitty gritty

Research at The University of Manchester has shown that changes in some components of the DAS-28 are influenced by our genes (the swollen joint count and blood markers of inflammation), but others do not seem to have a strong genetic influence (patient global assessment and tender joint count).

Another study found that using a simpler version of the DAS-28, which uses the swollen joint count and marker of inflammation only, is more successful in identifying genetic predictors of treatment response compared to the traditional score. So focusing on these aspects may give us a clearer picture as to whether our genes can predict response to treatment.

The genetic code provides instructions for making thousands of different proteins. These provide the building blocks for tissues which make up organs. Using scientific techniques, we can measure these proteins. In autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, there may be certain patterns in the profile of proteins that differ between patients that help us to predict response to treatment.

Target

My current research explores whether using genetic and protein markers collected in blood samples can predict if a person with rheumatoid arthritis is likely to respond to a certain treatment.

The project will analyse data collected in Maximising Therapeutic Utility in Rheumatoid Arthritis (MATURA), a nationwide initiative of academics, doctors and industry groups developing personalised approaches to treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. This work could provide insight into the mechanisms behind rheumatoid arthritis and why some medications may not work as well for different individuals. Research in this area could allow us to test of a combination of a person’s genetics and protein markers and identify which biologic drug is most likely to be effective for that individual. Ultimately, the goal is to develop a biologics calculator, where we can use a blood sample to personalise therapy for each patient.

The bottom line

Advancements in rheumatoid arthritis treatments have significantly enhanced quality of life for many. And now, groundbreaking research into personalised approaches, particularly through genetic and protein markers, holds the promise of even brighter days ahead, bringing us closer to a future where tailored therapies transform the landscape of rheumatoid arthritis care.