PhDs in Focus: Mini pancreata are fighting cancer

Welcome to our PhDs in Focus blog series, where our PhD students are showcasing their pioneering research projects at the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

In this blog, Manchester BRC PhD student Sofia Kochkina outlines how their PhD project aims to develop a laboratory model of pancreatic cancer that could be used to identify drugs capable of fighting it, as part of the Cancer Precision Medicine theme.

In the UK, more than 10,000 people are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer every year. Less than 10% survive this disease by more than 5 years.

The low survival rate is due to late diagnosis, cancer aggressiveness as well as poor efficacy and side effects of the current chemotherapy regimens. In most cases, pancreatic cancer rapidly develops resistance to treatment and relapses (comes back).

To develop better treatments and improve patient survival, it is critical to deepen our understanding of pancreatic cancer biology. How do pancreatic tumours grow? Why do they become resistant to therapy? These are the questions I am trying to tackle during my PhD at Systems Oncology laboratory at the Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute under the supervision of Professor Claus Jørgensen.

Why do we need a better cancer model?

Before a new drug is approved for use in patients, it must be proven safe and effective in a clinical trial – a research study conducted with human participants. However, to enter a clinical trial, the drug must undergo a preclinical evaluation to demonstrate efficacy.

Over the last few decades, several candidate therapies for pancreatic cancer have shown promising results in preclinical trials but have failed to benefit patients in clinical trials. This outcome signalled to the scientific community that the preclinical models currently used in preclinical research fail to completely replicate the complex biology of pancreatic cancer in humans. Therefore, to translate preclinical drug development into successful clinical trials, it is crucial to develop better laboratory models of human pancreatic cancer.

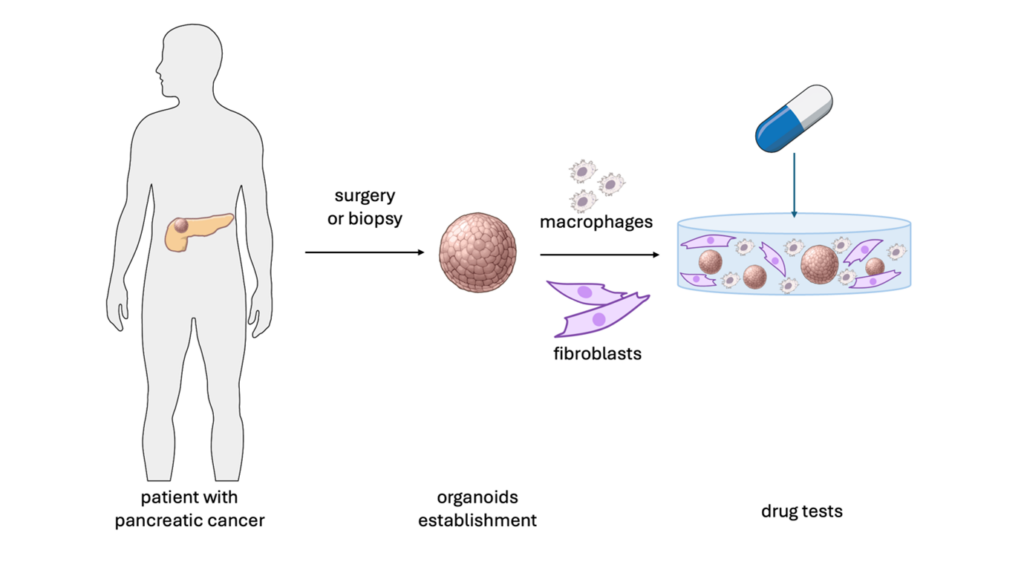

To address this need, the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) is supporting my PhD project where I am developing a novel test-tube model of pancreatic cancer for therapeutic testing. At the core of our model are pancreatic cancer organoids – miniature pancreata affected by cancer. Once the model is developed, we will be able to use it to identify candidate drugs capable of fighting the pancreatic cancer.

What is so special about our cancer model?

In my project, I focus on a model for the most common type of pancreatic cancer – pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). In PDACs, malignant cancer cells constitute only 10% of the tumour volume. The remaining 90% is composed of extracellular matrix (which provide structural support to cells) and non-cancerous cells, namely fibroblasts (which produce the extracellular matrix), immune cells and blood vessels. Previous studies have demonstrated that this non-cancerous part of the tumour has a role in therapeutic resistance, protecting the cancer cells from the drugs and shortening patient survival. Therefore, it is crucial that our model includes all parts of the tumour ecosystem:

- cancer cells

- extracellular matrix

- fibroblasts

- immune cells

Cancer cells

When someone with a pancreatic tumour undergoes a surgical resection or has a biopsy taken, they can donate a piece of their tumour to us for research.

The organoids we use in our research have been kindly donated to us either by patients with pancreatic cancer who have been treated at the Manchester Royal Infirmary, part of Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust or by our collaborators.

We extract cancer cells from the sample and embed them into a hydrogel designed to mimic the extracellular matrix of human PDAC. Due to the special media composition and the fact that cells are grown in 3D, over time spherical organoids are formed in the gel. Unlike the traditional 2D cell cultures where cells are grown on the bottom of a plastic flask, this approach allows for better reproduction of the ductal architecture of the pancreas and PDAC biology.

Extracellular matrix

The gel that I am using for my project is a product of a close collaboration between Systems Oncology and Professor Linda Griffith from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In addition to mimicking the protein composition of PDAC, this gel also reproduces the stiffness of these tumours. It is crucial to consider tumour stiffness when modelling PDAC, as elevated stiffness is its characteristic feature, and it has been associated with therapeutic resistance.

Other cells

Image created using NIH BIOART (https://bioart.niaid.nih.gov/)

Since cancer progression and therapeutic response are dependent on all the components of tumour ecosystem, we are now culturing cancer organoids together with immune cells and fibroblasts. We hypothesise that cell-cell communication within this microenvironment makes the therapeutic response of our model more representative of what is seen in patients.

Future work

Now the focus of my project is on the optimisation of the PDAC model for analysis of drug sensitivity. As a next step, I will investigate what determines therapeutic resistance in PDAC should it be tumour stiffness or involvement of the fibroblasts and immune cells. A better understanding of the underlying reasons for therapeutic resistance is the first step to overcoming it.

Finally, although this is out of the scope of my project, I believe that in future, the organoid model has the potential to be routinely used in personalised medicine to predict the best treatment plans to suit each patient.