Manchester BRC Biomarkers week – Proteomics

Manchester is a leading centre for biomarker development, brought together by the NIHR Manchester BRC’s biomarkers ‘cross-cutting’ research themes.

Our biomarkers research spans the fields of genomics, proteomics, clinical imaging, and biostatistics, and supports our mission to drive health improvements, and bridge the gap between new discoveries and individualised care.

What is proteomics?

Proteins are a fundamental building block of the tissue that makes up all living things, including humans.

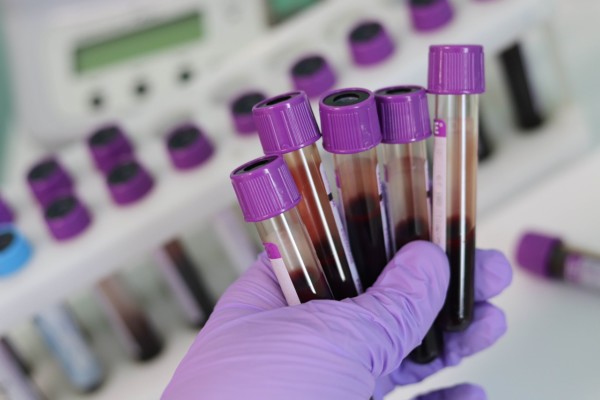

A proteome is a set of proteins produced by a living organism or system. This could be the whole of the human body, organs such as their liver or heart, or individual proteins found in individual cells or in the blood, which are often the most important for biomarker development.

Proteomes differ from cell to cell and change over time. The study of how these proteins react and change over time is called proteomics.

As a biomarker, proteins can be used in a number of ways to identify the presence of a disease, and predict how likely a patient will respond to treatment.

Professor Tony Whetton, Biomarkers Cross Cutting Theme Lead, said:

“Complex diseases, such as cancer, inflammatory conditions, and respiratory disease, trigger a significant physiological response in the body. This can often disrupt the production of specific proteins in the body, resulting in raised or lower levels than normal. Sometimes they can even stop production entirely.

“By discovering and isolating specific proteins and monitoring how they change over time, we can develop new tests to diagnose disease and help decide the best treatment for patients in clinics.

“This has the potential to tell us a great deal; from whether a patient has an early form of the disease when it is likely easier to treat, how advanced their condition is, how they might respond to current or future treatments.”

Proteomics in Manchester

Staff inside the Stoller Biomarker Discovery Centre

Manchester has cutting-edge facilities to support proteomics research, with the University of Manchester’s Stoller Biomarker Discovery Centre at the heart of this, led by Professor Whetton.

Based in Manchester’s unique Citylabs development, the centre aims to find and develop new protein biomarkers in blood and other tissues which help doctors ensure patients get the right treatment as early as possible.

The centre is equipped with several top-of-the-range mass spectrometry machines, the process used to isolate and identify proteins and other molecules by their molecular mass, as well as chromatography facilities used to separate different proteins and their constituents so they can more easily be analysed.

Manchester BRC’s Cancer Precision Medicine research is transforming care for patients, by developing new biomarkers to diagnose and monitor disease, to allow for more targeted treatments.

Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute’s (CRUK MI) Cancer Biomarker Centre (CRUK MI CBC) at Alderley Park is another leading biomarker facility. Led by BRC Cancer Precision Medicine Theme Lead, Professor Caroline Dive, their work focuses heavily on developing ‘liquid biopsies’ using circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) and circulating tumour cells (CTCs) in the blood, to inform decisions on patient treatments.

CTCs are shed from primary tumours, and can cause the growth of other secondary tumours elsewhere in the body (called metastases).

CtDNA can be used to identify biomarkers to diagnose and monitor various cancers, or even identify signatures that use several different proteins to estimate risk of developing disease, such as with ovarian cancer.

The CRUK MI’s cutting-edge Tumour Immunology and Inflammation Lab (TIMML) also analyses tumour samples for biomarkers, and helps to match patients to immunotherapy trials that may help to treat their cancer.

Professor Whetton continued:

“The Stoller is unique in Europe and has been assisting other BRCs across England to find biomarkers associated with their diseases of interest. This is essential to understand response to therapy and also risk of disease. Together with TIMML, they show the real research power of Manchester and our BRC in critical areas of research.”

Our proteomics research – VEGfi cancer treatments

Biomarker research for proteomics spans all of our clinical research themes. With studies looking at inner ear proteins to identify hearing loss from radiotherapy, response to therapy in rheumatoid arthritis, and new drug targets in leukaemia, proteomics is a crucial area of research.

Researchers in our Cancer Precision Medicine theme at the CRUK MI CBC have discovered a blood-based biomarker, which can monitor how tumours respond to drug treatment in patients with advanced ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, and biliary tract cancer.

These cancers form massive new blood vessels, known as angiogenesis, to supply their own growth and spread to other organs. These patients are often treated with drugs called anti-angiogenic VEGF inhibitors (VEGFi), to slow or stop the spread of blood vessels. Unfortunately the drugs are toxic and can increase the risk of high blood pressure and blood clots, and only work well on a proportion of patients.

A protein found in patient’s blood, called Tie2, has shown promise as the first biomarker to detect whether a VEGFi is successfully blocking a tumour’s blood supply. Our researchers are now running a study to monitor Tie2 via routine blood tests in hospital, to test whether patients will be able to start and stop VEGFi treatment at the right times.

Professor Caroline Dive, Cancer Precision Medicine Theme Lead, said:

“Manchester BRC’s Cancer Precision Medicine research is transforming care for patients, by developing new biomarkers to diagnose and monitor disease, to allow for more targeted treatments.

“On this initial study we worked closely with colleagues across both proteomics and clinical imaging. Together we were able to validate Tie2 as the first generic biomarker to monitor how a patient’s tumour is responding to VEGFi treatment.

“With the support of Cancer Research UK, we want to test this response for patients within a clinical setting and across other types of cancer. The hope is this will become a standard way to monitor patients, and improve their outcomes from treatment.”